Systemic Capacity

Seeing the System and Centering Community Experiences

After a culture of shared responsibility at individual and collective levels has been established, communities can work together to understand how systems have been designed and experienced. This understanding can uncover systemic goals and solutions, shifting burden from individuals and communities to educational systems and structures. Just as labeling students as “at-risk” encourages a limiting, deficit view of youth, labeling communities as “hard-to-reach” distracts attention from the need to redesign “hard-to-access” systems (Ishimaru, 2019). This last case story shows how even one policy change can spark a new understanding of how systemic structures are often designed to exclude and dismiss community experiences.

Centering Community Experiences Case Story:

Shasta County Office of Education

The Shasta County Office of Education (SCOE) developed a partnership with local tribal members as a result of the advocacy of the Local Indians for Education (LIFE) Center Director Rod Lindsay, who raised concerns about chronic absenteeism among Native American students to Superintendent of Shasta Schools Judy Flores. Local tribal leaders met with SCOE to identify a main cause of high absenteeism, leading to collaborative advocacy for Assembly Bill 516, which was signed into law in 2021 to amend the Education code to excuse absences for students attending cultural events or ceremonies.

This initial legislative goal inspired the formation of the American Indian Advisory, which is driven by a shared vision: to correct myths and misconceptions, to combat prejudice and promote appreciation, and to celebrate and honor the history, culture, and continuing contributions of Native Americans. Within the past few years, the Advisory formed a Lesson Study team of teachers who co-design History and Social Study lessons with tribal cultural consultants. This planning process enables tribal members to develop curricular narratives shaped by the wisdom and traditions of their own community, which is a powerful tool in combating deficit narratives that dominate mainstream curricula. Listen to the embedded clip to hear from Cindy Hogue, a Wintu tribal member who sits on the Advisory and serves as an 8th grade teacher in the county.

Click Here to ListenReflection

Superintendent Flores shared that the initial listening session with tribal members allowed her to recognize how tribal communities had never been granted access to leaders to share how neglected they felt – from attendance policies to instructional strategies. Think about the ways systemic exclusion might show up in your school or district.

Building Alignment and Coherence | Practicing Continuous improvement

A strengths-based, equitable approach to change requires that communities engage in a continuous improvement model that is responsive to community experiences and cultural wealth. The plan-do-study-act model of improvement science that is often implemented in schools and districts centers the collection of data at a level that is distant to the lived experiences of students, educators, and other community members. Street Data challenges the idea that data points like test scores are the best indicator of community strengths and needs, encouraging school leaders to seek an ultimate goal of well-being.

To ground their work, Safir and Dugan describe three levels of data that can make causes of systemic inequities clearer. Satellite data is helpful in identifying patterns of achievement and equity that can point towards an area for further direction. Datapoints at this level include academic, attendance, discipline, and graduation rates, which are a good starting point in a deeper investigation of the current state of the system. Map data such as rubric scores or community climate surveys are a better indicator of learning trends and opportunity gaps. These data points can be used to begin achieving more proximity to lived experiences, but street data are the most useful for understanding how a system is being experienced by different members of a community. Street data points such as focus groups, listening sessions, empathy interviews, and other activities for collective listening and learning support a more inclusive type of data collection, as these strategies uncover the types of cultural wealth that often go unrecognized by traditional metrics. When captured, these types of knowledge can be nurtured and built upon in classrooms, design circles, and more to build trust, strengthen relationships, and support a more equitable school system.

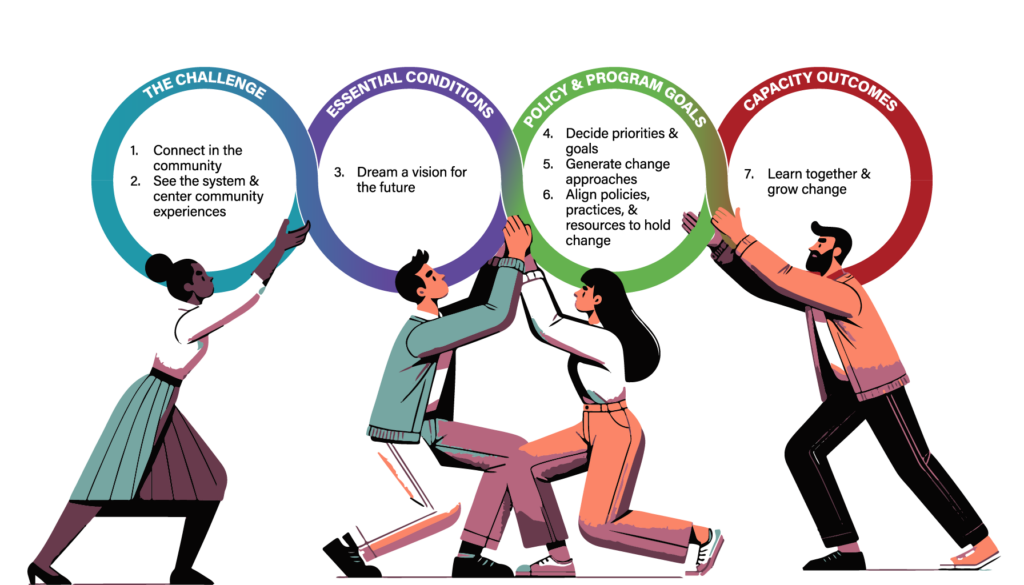

In Safir and Dugan’s equity transformation cycle, core values of inclusion, curiosity, creativity, and courage ground a process of improvement centered around street-level data. This model is built around the idea that complex change is nonlinear and emergent, or inherently unpredictable. To engage in this cycle, you should be prepared to listen deeply to voices at the margins in order to uncover true root causes of inequities. No matter what each school or district’s starting point is, the following questions can ground every transformation cycle:

- What is the equity challenge we need to address right now? Why does it matter?

- Which communities are most impacted by this challenge?

- How will we listen deeply to the voices and experiences of these communities? What types of street-level data will we collect?

Resources to explore:

- Ten Tips to Collect Street Data: A list of activities for gathering and learning from street level data

- Storytelling project model: A framework that can help groups analyze and understand how racism operates and impacts organizations, communities, and society

- Data for equity protocol: A protocol for helping a group reflect on data with an equity lens